Warships: Recreated in detail

Have you ever wondered about the accuracy and detail portrayed in video games – especially when it comes to games that purport to recreate historic battles or real-life vessels, vehicles, aircraft, weapons and so on?

Wargaming Group is very passionate about the details.

NOTE: This is not a ‘sponsored post’, but Wargaming has been good to CONTACT, with a drive in a real-life Centurion tank and a very spesh Christmas prezzie.

The following narrative was supplied by Wargaming Group – and published here because I am genuinely interested…

P.S. there are two more, equally interesting, related pieces, covering ‘naval manoeuvre‘ and ‘ballistics’ (coming soon).

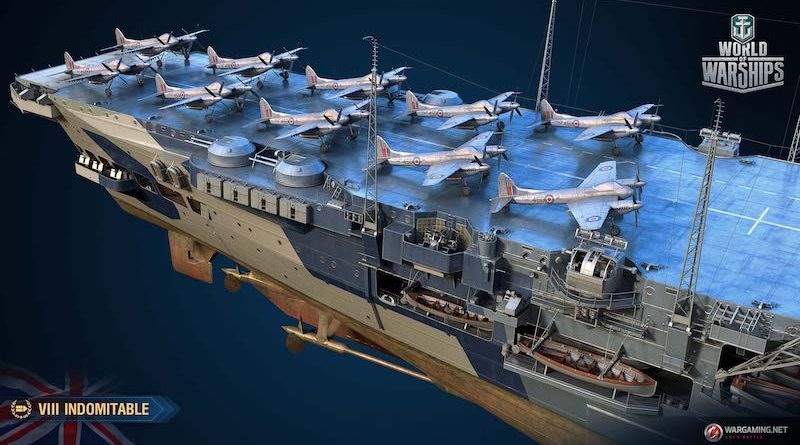

It goes without saying that the essential elements of any encounter at sea are, in fact, warships themselves. For that very reason, we’ve resurrected these steel monsters in the game, paying the utmost attention to their technological detail and making them as historically accurate as possible.

If any ship we’ve designed were ever to be recreated in steel, she would no doubt be able to plow the seas.

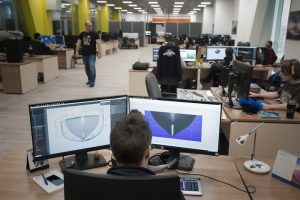

We’ve made it possible by adopting an extensive, multi-step process, ranging from careful examination of the available drawings and historical documents, to the creation of a fine-detailed 3D model of a ship where all the technological requirements are checked.

How We Collect and Process Information

In our game, warships are part of the overall gaming process.

When we select a project to work on, we’re primarily guided by input from game designers regarding the technical specifications and capabilities of a particular ship.

Once we’re certain about what kind of a ship we want in the game, we move on to gathering the necessary information.

- We collect all the available documentation about the target ship, including design plans, photos, designer sketches, and so on and so forth. In most cases, however, the documents that we come across are incomplete, so we have to “retrieve” the ship data bit by bit from other sources, such as any documents on other ships of the same type, the historical period, or the country of construction.

- We take the same approach when searching for data on all the major equipment to be placed on the would-be ship, including her armament, propulsion plant, aiming systems, cranes, cargo booms, lifeboats, and motorboats, as well as data on any materials and technology that might have been utilized on the ship.

All obtained data is collated and compared against data on other same-type ships. We use that data as the basis to elaborate a relevant, credible draft design for the ship. This way, we can identify any inaccuracies in the ship’s tech specs as early as at the data collection stage, which might then require us to reexamine the technical details.

When we design a ship, we don’t limit ourselves by looking only at her tech specs. We consider a variety of “non-numerical” information as well. These might be facts about how a ship’s design plans, prototypes, and her various equipment evolved over time; when and why various modifications were offered / implemented; or when various types of armament and equipment appeared or were adopted.

Placement of Key Equipment; Identifying the Main Particulars; Drafting the hull

During the early stages of the design process, we accommodate the key equipment on board the ship: the main and auxiliary propulsion plants, armament and the magazine sections, armor layout, aircraft hangars, catapults, lifeboats, etc. To do that, we create sketch plans for the ship’s decks, holds, superstructures, and the inboard profile. Those sketch plans are subsequently supplemented and finalized to be later used as the basis for final plans and drawings.

During the early stages of the design process, we accommodate the key equipment on board the ship: the main and auxiliary propulsion plants, armament and the magazine sections, armor layout, aircraft hangars, catapults, lifeboats, etc. To do that, we create sketch plans for the ship’s decks, holds, superstructures, and the inboard profile. Those sketch plans are subsequently supplemented and finalized to be later used as the basis for final plans and drawings.

We need to do this in order to ensure that all the equipment fits within the hull we’ve designed. For that purpose, we calculate mass loads, and verify the correspondence between the weight of the equipment and water displacement of the hull.

The ship’s hull is designed taking into account all the equipment to be placed within it. If the data doesn’t match, we either make changes to the composition of the ship’s equipment and its characteristics, or, if that’s not the best available option, we change the hull.

In the case of aircraft carrier Hakuryū, for example, we had to make the ship 20 m longer and 5 m wider compared to its prototype, G-15, so that the carrier could, in fact, “carry” her entire air group. The resulting increase in her water displacement forced us to adopt a different propulsion plant — one which we had to find.

The hull of a ship is selected by:

- Using the hull’s body plan if there is an available prototype with an appropriate hull.

- If the ship never made it to the completion stage in reality, or if no body plans are available, we refer to the specs of hulls of same-type or same-nation ships, scaled to match the technical specifications of the ship being designed.

For example, we utilized this approach when laying out the design for the hull of battleship Alsace. We scaled the hull of Gascogne evenly in length and width until it reached the required dimensions while keeping the hull height unchanged.

In cases where we aren’t able to find any suitable hulls, we draft a body plan from scratch using any plans that we have at our disposal.

We figure out the fairing characteristics of the ship’s hull, its water displacement, the position of the center of buoyancy, and other hydrostatic parameters.

Placement of Auxiliary Equipment

Finally, we arrange all the necessary equipment on the ship’s open decks and platforms.

In doing so, we keep an eye out for any intersections, overlapping, or blocks affecting the arrangement of equipment.

What we get as a result are the design plans for all necessary decks and platforms:

- The ship’s holds with positions for all key machinery, boilers, magazines, steering gear, armor, etc.

- Main deck.

- Design plans for all superstructure levels.

- Design plans for any platforms on masts and funnels.

- Inboard profile with a propeller screw / steering gear / shafts and boilers / machinery.

- Side elevation.

- Certain specific cross sections (as necessary).

The next part is pretty simple — the last step is to formalize the documentation.

Once all the above work is done, we are left with a ship that perfectly matches our expectations from a gameplay perspective, and that also corresponds to the actual historical facts and technological specifications.

.

.

.

.