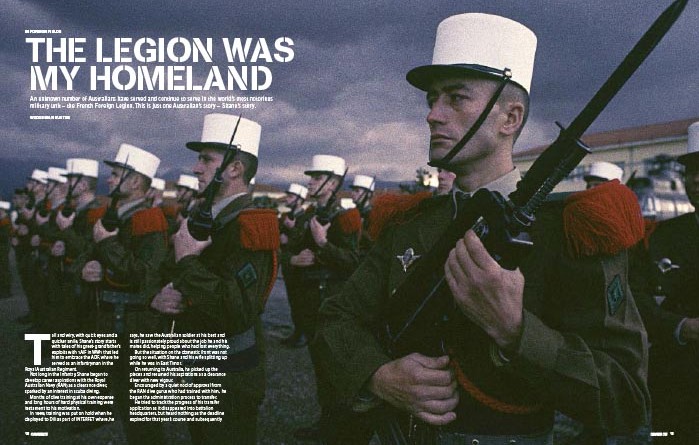

The Legion was my Homeland

An unknown number of Australians have served and continue to serve in the world’s most notorious military unit – the French Foreign Legion. This is just one Australian’s story – Shane’s story…

This ever-popular story was published in CONTACT Air Land & Sea issue 1, in March 2004. You can view it in its original form here.

Tall and wiry, with quick eyes and a quicker smile, Shane’s story starts with tales of his great-grandfather’s exploits with 1AIF in WWI that led him to embrace the ADF, where he served as an infantryman in the Royal Australian Regiment.

Not long in the infantry, Shane began to develop career aspirations with the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as a clearance diver, sparked by an interest in scuba diving.

Months of dive training at his own expense and long hours of hard physical training were testament to his motivation.

In 1999, training was put on hold when he deployed to Dili as part of INTERFET where, he says, he saw the Australian soldier at his best and is still passionately proud about the job he and his mates did, helping people who had lost everything.

But the situation on the domestic front was not going so well, with Shane and his wife splitting up while he was in East Timor.

On returning to Australia, he picked up the pieces and resumed his aspirations as a clearance diver with new vigour.

Encouraged by a quiet nod of approval from the RAN dive gurus who had trained with him, he began the administration process to transfer.

He tried to track the progress of his transfer application as it disappeared into battalion headquarters, but heard nothing as the deadline expired for that year’s course and subsequently finding it had never left his unit’s in-tray. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back and Shane threw in his discharge papers in frustration.

“My life was a shambles – my wife had left, taking my son, and I thought the Army had let my career down.

“I turned to the Legion because I wanted to do a real job – the same reason I joined the ADF in the first place.

“At that time, any Army would have done. I called a few, but the Legion was the first to make me a definite offer.”

He freely admits he knew very little about the French Foreign Legion before he set off for France, enlisting in Bordeaux.

“There was just me and a recruiting corporal. He kept asking me how much we got paid in the Australian Army – he seemed preoccupied with our pay and conditions.”

Shane says things were pretty relaxed at Bordeaux while waiting to go on to the next stage of selection at the Legions HQ at Aubagne where he would join more potential recruits from another 15 recruiting centres around France.

When he arrived at Aubagne one of the first English speakers he met was a Canadian, smoking pot in a crowded courtyard.

“I don’t think he had much of an idea. As we walked past a heaving beam he gave it his best fly kick – he didn’t last long and he didn’t get in,” Shane laughs.

“We were all wearing Kapooka-style blue track-suits and when not cleaning up we just sat around waiting to be processed or rejected.

“If you’re not doing selection stuff you’re cleaning shit that’s been cleaned a million times already and if you cleaned the floor any more you’d slip on it – but you do it anyway.”

Every day the number of recruits got smaller, but the routine was a familiar hurry-up-and-wait.

At this early stage, Shane started to notice how the different nationalities stuck together. The biggest group appeared to be from the former Soviet Union and the majority of them appeared to be there for a standard-of-living improvement. They were christened the Russian mafia.

“The Asians were pretty quiet. They kept together in a small group away from everyone else and, being small guys, it was easy to see they were intimidated.

“It seemed most recruits joined for a new life. They didn’t want to volunteer for the paras or snipers. Nor did they want to carry a heavy pack. They didn’t want to work for it – they just wanted the money and a French passport to a new life.”

Food at Aubagne was pretty simple – “lots of bread, but not that bad.”

After passing three weeks of selection at Aubagne, Shane and his fellow recruits arrived at Castlenaudary to begin basic training. But, as training progressed, Shane started to notice little things, and to silently question the professionalism of the organisation he was to serve in for the next five years.

“They didn’t teach us anything like marksmanship principles and I had serious doubts about the standard of marksmanship the Legion was producing.

“Other training was very basic as well. For example, first aid was non-specific, unlike Kapooka where one of the first things you learn is CPR and trauma. But in the Legion, training was rudimentary to say the least.”

It was this non-specific approach to a fundamental life-saving military skill that was to spell tragedy and ultimately mean the end of Shane’s career in the Legion.

Teaching methods consisted of, demonstrate, imitate and a whack to confirm.

“A whack from the staff meant you soon picked up the language, watching and listening to what was happening around you.

There was no free time. There were no washing machines. Everything was done by hand, in sinks – without making a mess.

If Shane questioned the professionalism of the Legion’s teaching methods, he was however impressed by its French-only officers.

“One night out in the countryside, we got dragged out of our sleeping bags after a 60km march because the picket had fallen asleep.

“They had us leopard-crawling through snow and stinging nettles, in our undies, doing push ups in a freezing river – the whole deal.

“And, the officers were there with us – putting in. They didn’t have to, but they led by example – unlike some I had worked with back home.”

After a month at Castlenaudary the recruits became Legionnaires and received the prestigious Kepi Blanc – the symbol of the French Foreign Legion. But Shane says he had other things on his mind that night.

“The colour of my hat didn’t bother me, I just wanted to do a job. It meant little to me by then – my feet were fuckin’ sore from marching 60km to the ceremony. But a lot of the young guys were excited about it.”

As training progressed, Shane formed a friendship with the two other ‘Anglos’ – Dooley, a former South African police officer, and Morgan, a former Royal Air Force air-crewman.

Shane says Morgan had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions in the first Gulf War, but had problems adjusting to life after the war and was looking for a new challenge.

The three native English speakers began to stick together more than ever, as the mafias became more prominent.

“It was a survival thing. We were on our own. We didn’t have a ‘mafia’.

“If there was a duty to be done, do you think the Russian corporal was going to give it to the Russians? No. And so it went on. There weren’t any ‘Anglo’ corporals, so we copped all the shit.

“My Polish section commander, Cpl ‘Bad-nutz’ hated the ‘English’. Every time he saw me he wanted to hit me.

“He was a full-on Nazi. He was a hard man who, I think, was trying to harden us up, and I came to respect him for that. He was a very good soldier – someone I would want next to me when the shooting started.

“However, I question his ability to draw the line when using force. He could be a real arsehole.”

Men fight – always have done – and you have to be prepared to do it to them before they do it to you if you want to survive and be a man amongst men, especially in an enclosed area like Castlenaudary.

But on one fateful day, the three ‘Anglo’s’ future careers with the Legion went into free-fall.

The series of events started with Dooley breaking his back in a skiing accident while training in the Alps, and would lead to his eventual medical discharge.

Later that day, the platoon and its training staff took the night off from mountain warfare training to let off some steam in a remote Alpine pub.

“We’d managed to have a night on the piss during training, away from the barracks. It was pretty full-on – loads of piss and a stripper.”

Shane says that during the night, one of the Russians threw up all over a table and his ‘mafia’ forced a Portuguese Legionnaire to clean the table while the Russian went to the toilet to clean himself up.

“I respected the Portuguese bloke – he was a nice guy. The men in his family had all been Portuguese firefighters and he tried to follow in their footsteps but was turned down. I think he joined the Legion to prove something to himself and to his family. He was a good kid. He didn’t deserve to be treated like that. So Morgan followed the Russian into the toilet and gave him a good beating.”

Unfortunately for Shane and his offsider Morgan, things escalated from there and it signalled the start of a sorting out of who was who in the zoo. Grudges surfaced, scores were settled and reputations were on offer.

Until that night Shane had had no social contact with his platoon sergeant, but now Shane, Morgan and the platoon sergeant were drinking heavily together and swapping stories.

As the night wore on, the pub became a pressure cooker of testosterone and alcohol.

The platoon sergeant, now stirred by alcohol and the fighting going on around him, wanted some action of his own and challenged Shane to a fight away from the eyes of the platoon, with no repercussions and no questions asked.

With a drunken, mischievous, devil-may-care attitude, Shane agreed and the sergeant removed his brassard as the two men walked out the door.

Outside Shane turned to face the sergeant who had conveniently found two wooden batons, which were already approaching Shane’s head at a rapid rate.

Like the flick of a switch – thanks to long hours of military unarmed-combat training back in Australia – Shane applied a few choice moves and the sergeant went down and stayed down – but not before biting Shane’s ear almost through.

Soon after, other SNCOs and Legionnaires came out to view the spectacle – but it wasn’t what they expected, with the heavily bleeding Legionnaire standing over the broken Russian sergeant.

Not knowing that it was, in fact, just two consenting men having a bit of drunken rough and tumble, the other SNCOs presumed the platoon’s hierarchy had been turned upside down.

To cut a long story short, the party was over and the rest of the platoon were quickly loaded on to trucks for the trip back to base. Shane and Morgan, however, were siphoned off to a separate truck where they waited alone in the dark.

When a mob of Russian Legionnaire’s boarded, the tension became unbearable. Shane and Morgan understood that, one way or another, it was going to be a bumpy ride home.

The two ‘Anglos’ decided to break the ice by singing Waltzing Matilda as loud as they could, further incensing the Russians who, with the support of training staff, were not going to lose any more national face.

As the truck picked up speed, the Russians wasted no time, and hooked in with fists and boots. Although out numbered, Shane and Morgan gave as good as they could. However, things got a lot worse when Morgan disappeared, head first, over the speeding truck’s tailgate and into the darkness of the French Alps.

There was pandemonium as the men tried frantically to alert the driver to stop. Shane managed to get to the unconscious Morgan first – but it was too late. Lying in the road, his friend had suffered massive head and neck injuries from the beating and the fall.

Experienced in first aid, Shane began EAR and attempted to control the bleeding only to be pushed aside by a panic-stricken Russian SNCO who was shaking the dying Englishman’s head and shoulders, screaming , “Souflee Morgan, souflee” (breathe Morgan, breathe).

Reeling in shock at the unprofessional behaviour of these supposedly elite soldiers – Shane wondered was this what he really aspired to become?

Nearly three hours later an ambulance arrived, but on arrival, the medics didn’t fully comprehend the injuries and, Shane says, that without any doubt, their resulting treatment did not help.

Morgan later died in hospital.

On returning to base, Shane was ‘interviewed’ with fists and kicks by everyone who had something to lose from the results of an impending inquiry into Morgan’s death and, locked in a room, he was unable to give a statement to the investigating French Police.

Now without his two mates to watch his back, and very much out of favour with the training staff, who made sure Shane was kept busy with never-ending menial cleaning duties, Shane realised he didn’t want the type of soldiering the Legion was offering.

“I wanted controlled aggression, discipline. And I wanted to work with professional soldiers,” he says shaking his head.

Shane requested the termination of his contract at the end of the Legion’s authorised six-month cooling-off period.

“After they knew I was serious about leaving, the system took over and things were OK.

“Funnily enough I ended up in the discharge room with Dooley, who was being medically discharged because of his broken back but which didn’t stop training staff allocating him strenuous cleaning duties.

“A former Belgian paratrooper and a former German Special Forces guy were also there.

In fact, all my platoon’s former professional soldiers were in the discharge cell.

“Maybe that tells you something about the type of person who didn’t want Legion life.

“I have no regrets, though. I met some good guys who I still keep in touch with, I learnt a new language, bits about other cultures, new skills – and my fitness was awesome,” he laughs.

Shane’s advice to potential Legionnaires?

“If you must do it, do it while you’re young.

“But, the type of guy who joins the Legion won’t listen to other people’s advice anyway. He has to experience it for himself, first hand.”

Facts of life in the Legion

The reality of ‘romantic’ French service

- King Louis Philippe raised the French Foreign Legion in 1831 as a fighting force of foreigners to serve French colonial interests.

- The only Frenchmen officially allowed to join its ranks are officers. However, Frenchmen do join, but alter their nationality on enlistment, for example to Swiss or Canadian.

- Today’s French Foreign Legion is 8500 strong, in 11 regiments based on the same order of battle as the French Army, with the same equipment and military laws – except that no women are permitted to serve.

- Seven regiments are based in France with the rest overseas in Djibouti, French Polynesia, Mayotte in the Indian Ocean and French Guiana in South America.

- The Legion has the same entry standards as the regular French Army – poor eyesight, hearing and fitness are screened out.

- Of the 12,000 men a year who want to be “a man amongst men”. Only one in 12 is accepted.

- 130 countries are represented in the ranks. The Legion views this cultural melting pot as its strength. Officially members have only one nationality, that of Legionnaire, as reflected in the their motto Legio Patria Nostra – the Legion is our homeland.

- The myth that authorities turn a blind eye to serious criminals joining the Legion in exchange for dirty deeds done dirt cheap, is not the case – any more. IDs are processed by the Legion’s security section who liaise with Interpol to weed out wanted criminals.

- Compared to times past, the Legion doesn’t need the hassle from the authorities. They can now afford to pick and choose, as the disintegrating former Soviet empire has provided plenty of ‘clean’ recruits eager for bed and board and a French passport to the West.

- The Foreign Legion is reputedly the only institution where a man can be truly reborn, and it’s at Aubagne you can choose to change your name and leave history at the gates. Recruits can be issued a new name or later, their original identity through a process called rectification.

- Legionnaires receive the same pay as regular soldiers of the French Army with the usual sliding scale in pay according to rank and length of service. Bonus pay is earned according to posting. Starting pay for a Legionnaire is 1040 Euro per month paid into an account of his choosing.

- After 15-years service, members qualify for an Army pension, payable in any country.

- Vehicle ownership prohibited – even push bikes.

- Eight men to a room normal for barrack accommodation. TV, VCR and bar fridge are allowed.

- Only single men may enlist, but marriage allowed after five-years service – with permission.

- Civilian clothing never to be worn except on annual leave.

- 15-45 days paid annual leave must be spent in France, except by hard-to-acquire permission.

- Intrusion into daily life means most Legionnaires only serve the basic five-year contract, which begins when he arrives at one of the Legion’s 16 recruiting centres spread throughout France.

.

.

.

.

there must be 1001 reasons why a man never honours his 5 year contract, i must have heard at least 950 of them. Remember this… “you go to the Legion, the legion doesn’t come to you” Ossie O, 2REP 1989-94

Yep, Tommo is right. I served from 84-89 and tons of weaklings quit then go home and big it up about the brutality and conditions so they can justify the fact they quit.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again – feel free to attack what was said in the story, but I will not tolerate attacks on the person – not this person and not any person.

As I said to Tommo – I respect your opinion, Nick, as much as I respect Shane’s. He has as much right to say the things he did as you do to say (some of) the things you said. To that end, if you want to write a story about your time in the Legion, I’d be more than happy to publish it. But I will not allow it to get personal.

Brian Hartigan

Editor

I was attacking what was in the story Brian…by HIS own admission his marriage failed, his time in the Aussie army was a fail, and his time in the Legion was a fail. I didn’t say that…HE did. I was just pointing out that there is an underlying current of failure there on HIS behalf, and therefore the blame should probably be laid on his doorstep and not the Legion’s.

That is the biggest load of Bollox I have I ever read on the Legion.

For your information I served 1985-1990 at age 18 at the height of bastardisation in the Legion.

At a scrawny 60Kg and 167cm I never saw the shit he is describing.

Really pisses me off when I read half baked bull shit like this from blokes who chucked it in at end of probbie so they got home and had an excuse and a story to tell.

Tommo. I respect your opinion as much as I respect Shane’s. He has as much right to say the things he did as you do to say (most of) the things you said. To that end, if you want to write a story about your time in the Legion, I’d be more than happy to publish it.

BTW, you may notice I deleted the last line in your comment. While you are entitled to have a differing opinion to someone else and you are entitled to attack the things he said (up to a point), personal attacks are not OK.

Brian Hartigan

Editor