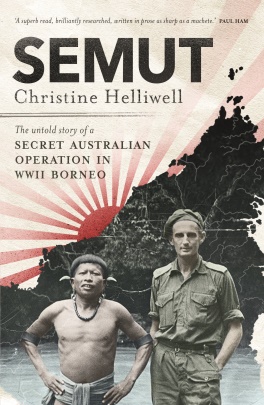

Book Review – Semut by Christine Helliwell

One of the ongoing ironies of war is that it has been and remains a catalyst for great literature. Semut by Christine Helliwell follows this fine tradition. As Paul Ham notes on the cover – ‘A superb read, brilliantly researched, written in prose as sharp as a machete.’ So it is most apt that the epigraph at the start of the book is from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Not only is the setting and psychological tension similar, jungle covered mountains interspersed with mighty raging rivers and a loss of innocence, but the style is equally evocative. Christine’s description of Borneo: ‘resting languidly across the equator … with the meandering flotilla of Indonesia to the south’; and the countryside – ‘all around were endless battalions of trees, marching from the riverbanks to the distant hills’ – takes one back to another era and another place. Likewise her description of the reconnaissance teams parachute insertion into Borneo awakens fading memories of similar experiences:

‘The Liberators crossed the coast of British North Borneo into enemy airspace around dawn, the rugged mountains of the interior directly ahead in the growing light. Reaching the sandstone and shale mass of Mt Mulu, second-highest summit in Sarawak, they turned southeast towards the great peaks of the Tama Abu Range. And there, as expected, gleaming white in the morning sun, were the twin fingers of Batu Lawi. As the nervous tension ratcheted up, the planes came over the range and into the air above the valley. And hallelujah, for the first time the pilots had clear sight of the drop zone. The Semut men were already up, stretching, adjusting their parachute harnesses, moving to the bomb bay out which they would be despatched, the Liberator crew joshing them, as was customary in such times of tension. The plane commanded by Pockley stalled, with consummate skill, over a stretch of inviting grassland below, and dropped its human cargo of four.’

But the strength of this account over all others is that it also looks at the story from the perspective of the local indigenous inhabitants:

‘It was early morning when Keling Langit heard the sound again. The young Kelabit woman paused at her work amid the cool slush of the rice field. Yesterday’s eerie echo had returned, moving back and forth above the clouds that hung across her valley high on the Kelabit Plateau. It was like nothing she had ever heard before: quite different from the rhythmic whooshes of the hornbills’ wings as they flew across the valley in the evenings, or the slowly climaxing whoops of the gibbons as they called to one another in the jungle trees at dawn. This was a strange reverberating roar that filled the valley, overwhelming all other sounds. Peering skyward Keling Langit saw, to her horror, several giant white figures materialise through the cloud. They resembled the pale spirit beings said to have once inhabited the area, their superhuman exploits remembered in song during long evenings in her Bario longhouse home. Closer and closer they came, descending slowly and silently like birds stooping to land. Keling Langit felt such terror that she began to weep.’

While elements of Operation Semut have been told in the past, the activities of the Semut II and Semut III parties have never before been fully researched or properly examined. This book brings closure to this small but important and very unique chapter in Australia’s and the region’s military history. The book is the first of a planned set of two, and covers the background, planning, wartime history, strategic and political drivers, personal recollections, and tactical actions of the special operations conducted by the Services Reconnaissance Department (also known as Special Operations Australia and manned primarily by personnel from Z Special Unit) in Sarawak from March to October 1945. Importantly it also provides an overview of the colonial history of Sarawak, the ethnic groups inhabiting the land: their enmities and alliances; cultural and spiritual beliefs and living conditions; and their motivations for joining the allied cause. As such it is more than a military history; it is also significant resource for all with an interest in understanding guerrilla or more specifically special warfare (that is the sponsorship and use of irregular indigenous forces in the prosecution of military operations against a common foe).

While the world and warfare has changed significantly since 1945 many of the lessons, especially those relating to Guerrilla/Special Warfare outlined in this book remain relevant today. At a personal level the importance of humility and humour; the need for toughness of body, mind and spirit; and critical role of local knowledge and a common language, usually theirs not ours, stand out. Likewise the need for special operations teams to have dedicated transport assets, whether air, land or sea combined with reliable communications are reinforced. And more importantly the need for the conventional and unconventional forces to have common and supporting objectives when operating in the same theatre is and will remain paramount. Finally political and military leaders, planners and operatives need to understand that at its core Guerrilla/Special Warfare is inherently political and that while military success is important so too is the need to harness and protect the civilian population. For without their support there can be no guerrilla movement and while you might win the battle without them you will not win the peace.

But perhaps the most striking aspect of this story is the dilemma presented by the conduct of headhunting by the indigenous guerrilla forces and the potential for critics to accuse the author of engaging in moral relativism for explaining and in part justifying the practice. By way of explanation “the term ‘moral relativism’ is understood in a variety of ways. Most often it is associated with an empirical thesis that there are deep and widespread moral disagreements and a metaethical thesis that the truth or justification of moral judgments is not absolute, but relative to the moral standard of some person or group of persons.” This is highlighted in the following account of an early raid conducted by Semut II:

‘But then, disaster: sudden movement and a light not far from the fort – the radio hut! A voice sprang shockingly out of the murk, then more movement and another shout. With the element of surprise lost, Sheppard hoisted his gun and began to fire on both fort and hut. Those with him followed suit, producing a massive burst of gunfire. They were almost at the fort when a Japanese soldier ran out of its door immediately in front. Pipen shot him dead at almost point-blank range. There was now pandemonium: in the dim light it was difficult to tell who was friend and who foe. The Kayans and Kenyahs (Dayak tribes) nevertheless moved quickly to surround the two buildings, in line with their instructions … Other Japanese fell: some to gunfire, some to parang … And then, quiet: profound in the wake of the noise and confusion … Sheppard called his troops to order on the clear ground beside the fort. It was then that he noticed: two of them held human heads.’

It is not for me in this review to make a judgement either way, but the case presented in the book is compelling and highlights the physical, mental and ethical complexities of the battlefield, especially when isolated and working with personnel who have different cultural and spiritual beliefs and practices. The historical context must also be remembered. As the author notes – “all wars are cruel, but the war against the Japanese throughout the jungles of the Pacific – including Borneo – was especially so. ‘Kill or be killed. No quarter, no surrender. Take no prisoners. Fight to the bitter end. These were everyday words in the combat areas. As World War Two recedes in time and scholars dig at the formal documents, it is easy to forget the visceral emotions and sheer race hate that gripped all participants.’”

Professor Helliwell is to be congratulated on writing such a fine book. I have no doubt that it will become a classic and be highly prized. Semut by Christine Helliwell is highly recommended. In fact it is a must read.

.

.

.

.