War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART II

Share the post "War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART II"

Part II of a two-part essay titled War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – the trial of Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton – Relevance to ADF War Crimes Investigation. Part I is published here.

By James Unkles

There were flaws in the arrest, investigation, trial and sentencing of Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton in 1902.

The following issues were identified:

- Denial of natural justice. A court of Inquiry commenced on 16 October 1901. On or about 22 October 1901, Morant, Handcock and Witton were arrested and placed in solitary confinement over allegations of shooting Boer prisoners. The accused were denied details of the investigation, no opportunity to seek legal advice, cross examine those who gave evidence at the investigation or conduct their own inquiries and arrange defence witnesses. The denial of legal advice continued until the evening before their trials commenced on 16 January 1902. The lack of time to consult legal counsel was a gross injustice noting the seriousness of the charges.

- Denial of fairness to prepare defence cases for trial. The prosecution had three months to prepare cases against the accused before trials commenced in January 1902. This was in stark contrast to Morant, Handcock and Witton who were denied the right to consult legal counsel until 15 January 1902. One day’s preparation before trial to seek legal advice on serious allegations and complex legal issues with defence counsel Major James Thomas, with whom they had no previous contact. Their confinement and limited time to prepare a defence included locating and interviewing witnesses. This prevented them from mounting a defence to charges of murder. The denial of fairness was a serious breach of military law and procedure in accordance with the Manual of Military Law 1899.

- Condonation. The application of condonation should have caused pardons to be granted to the accused at the time of the trials or after their convictions but before sentences had been carried out. Condonation arose from the call to service during a Boer attack on Pietersburg on 23 January 1902 and again on 31 January 1902. Condonation should also have been recognised as a plea in bar due to the offences being condoned or pardoned by a competent military authority.

- Trial Errors by Judge Advocate. The members of the courts martial were not properly directed to a competent standard by the judge advocate on issues including:

- The lawful excuse of obedience to superior orders, evidence of provocation, evidence of the accused’s limited military service;

- The status of the accused as volunteers and their limited education and ignorance of military law;

- The significance of mitigating circumstances and character evidence; and,

- Several failures in trial procedures directions on matters including, sufficient time and resources to prepare a defence to serious charges of murder and to ensure the accused were not unfairly restricted in their rights to a fair trial.

- Review of convictions and sentences. Lord Kitchener, the confirming authority of convictions and sentences failed, amongst other things;

- to inform the accused of the verdicts and sentences within a reasonable time so they could seek legal counsel on their rights of review through the military redress of wrongs procedure or petition to the King;

- to ensure that he was available in Pretoria after he had confirmed the sentences and convictions on 25 February 1902 to hear pleas for mercy by the accused and their counsel;

- to ensure the accused were permitted to contact their relatives and/or representatives of the Australian government to seek clemency on their behalf (this failure was particularly cruel and unjustified); and,

- to ensure the accused were not prejudiced in their defence or suffered injustice during the investigation and trial proceedings.

- In addition to the above failures, Lord Kitchener arranged or countenanced the posting of Lieutenant Colonel Hall, the area commander for Spelonken, from South Africa to India, thereby preventing him from giving evidence at the investigation and trials on issues such as orders to shoot prisoners. This action caused extreme prejudice to the accuseds’ defence of obedience to superior orders.

- Unsafe verdicts. In all the circumstances, the convictions and sentences were unsafe. Posthumous pardons are needed to address the substantial errors and injustices and to quash the convictions.

The evidence has since been considered by three Australian attorneys-general, Robert McClelland, Nicola Roxon and Mark Dreyfus.

In 2011, Mr McClelland announced that these men were not tried according to law – however, his decision to make his concerns known to the British government was not completed.

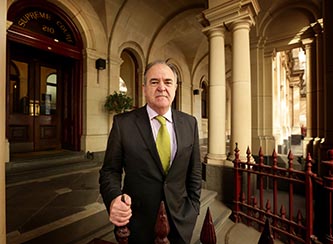

In a significant step towards judicial review, I put the evidence before the Victorian Supreme Court on 20 July 2013.

Although it carried no judicial standing, the ‘moot hearing’ was conducted professionally by senior counsel who acted for the Crown and the accused.

The case was heard by senior barristers Andrew Kirkham, RFD, QC, and Gary Hevey.

They found unequivocally that the men had not had proper trials and had suffered a substantial and fatal miscarriage of justice.

Those interested can view the hearing on line at breakermorant.com

Renowned and respected human-rights lawyer, judge and author Geoffrey Robertson’s, AO, QC, opinion (2) was also supported by former Chief Justice of the NSW Supreme Court Sir Laurence Street, AC, KCMG, KStJ, QC, and former Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer AO.

They agreed that the case represents a gross miscarriage of justice and is deserving of independent inquiry.

Calls for review have also come from other judicial officers, including Dr Howard Zelling (deceased), former Chief Justice of South Australia Charles Francis QC (deceased), David Denton SC, Judge Sandy Street SC and MPs Alex Hawke, Greg Hunt, Tony Smith and the MPs who were members of the House of Representatives Petitions Committee.

Their calls for judicial review cannot be ignored.

Matters of justice confront government, none more important than Australia’s defining principle of being a fair and equitable country and its values of embracing democratic principles.

Foremost is Australia’s tradition of trial according to due process to ensure that those appearing before courts are presumed to be innocent and entitled to a fair and unbiased hearing in accordance with statute and common law.

For 118 years, the issue of whether Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton, were tried according to British law and treated fairly when convicted and sentenced for shooting Boer prisoners has been one of Australia’s most enduring controversies.

Many will not be aware that, since 2009, a dogged war of a legal nature has been waged by me in an effort to persuade the British or Australian governments to comprehensively review the case.

The execution of Morant and Handcock on 27 February 1902 and the sentencing of Witton to life imprisonment continues to ignite passionate debate in Britain, South Africa and amongst their Australian descendants.

The brutality of the Boer War in British military history is one that many – particularly in London – would rather forget.

In the midst of the war, the trial of these three volunteers highlighted reprehensible tactics ordered by British officers, including reprisal through summary execution as a means of prosecuting the war.

It has been argued convincingly with persuasive evidence that the Australians shot 12 Boers while acting under the orders of senior British regular Army officers, including Lord Kitchener.

Putting that aside, the process used to try these men was illegal and improper and was done to hide the criminal culpability of British officers.

Put simply, the accused were not afforded the rights of a person facing serious criminal charges enshrined in military law and procedure of 1902.

Perhaps the opinion of Australian government minister Greg Hunt MP (5) will ensure the injustice is addressed: “My view is that any Australian government at any time should seek final resolution, and if we are elected then I will continue to work within the parliament to see that outcome. I think the concern is that two Australians were executed in a summary fashion without justice. None of this excuses what was clearly a heinous act in relation to the prisoners under care, but it is time, in my judgment, for a proper independent inquiry. That may not change the decision of the court, it may reverse the decision, or it may say that there were mitigating circumstances that these were actions taken under orders. But there was no justice, there was a summary execution after a sham trial and there deserves to be a full trial. This will not ever excuse their actions, but similarly it is clear that the actions of the colonial administration of those who were running the Boer conflict were equally reprehensible. And if there is a stain on the historic record, we need to address it“.

Mr Hunt’s assessment is supported by noted jurist, Sir Laurence Street (6), former Chief Justice NSWs (deceased): “I think the British government should intervene and appoint an enquiry, the outcome of which I’m sure would be that the conviction should not be allowed to stand and would quash the convictions. This is an appalling affront to any general notions of justice, and an appalling injustice to the remaining living man. This was an exercise of the administration of criminal justice which sadly miscarried. No judge with any ownership of the criminal justice system in his jurisdiction, or her jurisdiction, could tolerate something of this sort going unremedied. This is crying out for judicial intervention“.

These opinions were reflected in an historic motion that was drafted by me and moved by Scott Buchholz MP in the House of Representatives on 12 February 2018.

The motion concluded that the men were not tried according to law and expressed sympathy and regret to the descendants.

The motion was compelling and reflected Mr Buchholz’s commitment to see justice done: “Lieutenants Morant and Handcock were the first and last Australians executed for war crimes, on 27 February 1902. The process used to try these men was fundamentally flawed. They were not afforded the rights of an accused person facing serious criminal charges enshrined in military law in 1902. Today, I recognise the cruel and unjust consequences and express my deepest sympathy to the descendants“.

As Australia enters the landscape of assessing and trying alleged war crimes by Australian SAS soldiers, Leo D’Angelo Fisher’s review (3) is an opportunity to remind us that the outrage of perceived war crimes can be equally outraged by the abuse in human rights in the arrest, detention, trial and sentencing of offenders.

This applied in 1902 and in the present and must remain the focus in the conduct of military justice.

Anything less is a failure of leadership.

I remain committed to having the Morant matter independently examined and justice delivered posthumously so that Major Thomas’ work can be completed and the descendants of these men can rest knowing that the injustice done has been addressed and this case of Australian military and legal history resolved.

Corrupted trial process makes martyrs and this case is a clear example.

The passing of time and the fact that Morant, Handcock and Witton are deceased does not diminish errors in the administration of justice.

Injustices in times of war are inexcusable and it takes vigilance to right wrongs, to honour those unfairly treated and to demonstrate respect for the rule of law.

This matter involves injustice – and how we respond is a test of our values and treatment of these Australian veterans.

Their descendants and those who respect the rule of law await justice and that must be put above all other considerations.

The words of former Deputy PM Tim Fischer (7) (deceased) aptly addresses the injustice: “Because two great wrongs were done to both Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock – absolute wrongs – and also a wrong towards George Witton – and this goes to the moral values and fabric of a nation – we know these wrongs were done – do we do nothing about it, or do we in fact seek to at least – we can’t reinstate life – correct the formal record by one method or another here or in Great Britain“.

There are lessons to be learnt from the Morant matter in light of the current war crimes investigation.

Will the process of fair trials be rigorously applied without prejudice to any accused?

Will our political leaders and senior ADF leaders including CDF and CA act in an appropriate manner to ensure scapegoats are not made of junior personnel to cover the complicit action of commanders and leaders in Canberra?

We will wait and see what eventuates, but the scrutiny by the ADF and veteran community must be resolute and call out perceived injustices.

Part I of this essay was published on Monday 14 December 2020

James Unkles

James Unkles

is a civilian lawyer, military reserve legal officer (Rtd), petitioner for the descendants and author of Ready, Aim, Fire: Major James Francis—The Fourth Victim In the Execution of Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant – Sid Harta Publishers, available online at Booktopia or by contacting the author via jamesunkles@hotmail.com

Please also visit www.breakermorant.com

.

.

REFERENCES:

-

- Lord Kitchener cable sent to Secretary of State on 6 April 1902 aptly summarises the case for review in the Breaker Morant controversy.

- Geoffrey Robertson QC, International Jurist and Human Rights advocate, 2013 interview with James Unkles.

- Leo D’Angelo Fisher, War-crime allegations are confronting but they may lead to welcome reforms, Australian Veteran News, 7 June 2020.

- Witton, George, Scapegoats of the Empire, Angus and Robertson, 1982.

- Greg Hunt, interview with James Unkles 2013.

- Sir Laurence Street AC, KCMG, KStJ, QC, interview with James Unkles 2013.

- Tim Fischer, AC, extract of interview with James Unkles 2013.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Share the post "War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART II"