RAMSI – Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands

Share the post "RAMSI – Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands"

The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands – RAMSI – officially ends today, 30 June 2017, after nearly 14 years of assistance provided to the Solomon Islands Government [see news item here]

CONTACT Editor Brian Hartigan, then working as an Australian Federal Police photographer, was the first person off the flight that took the Australian Federal Police main contingent to Honiara on 24 July 2003.

Over the following 32 days, Brian Hartigan captured some of RAMSI’s (and AFP’s) most iconic and enduring photos.

Today, as the mission ends, we republish a magazine feature CONTACT published in September 2005, and re-publish some of Brian Hartigan’s favourite photos from the first month of RAMSI.

WORKING TOGETHER FOR PEACE AND STABILITY

By Kathryn Fitch

re-edited by Brian Hartigan

Photos by Brian Hartigan (for AFP)

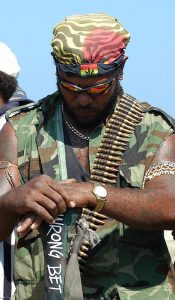

In 2003, rival ethnic militant groups had made the Solomon Islands a no-go area – thugs with guns ruled the capital Honiara, the Prime Minister was living in fear of his life, and the government was effectively bankrupt, the Royal Solomon Islands Police (RSIP) had broken down under the pressure, struggling with internal corruption and unable to match militant firepower.

Following an appeal for assistance from the Solomon Islands’ Government, a combined force of Australian soldiers and police arrived on 24 July 2003 to a warm welcome from the locals. RAMSI comprised a whole-of-government response from Australia, as well as police contingents from 11 countries and military support from five countries.

Assistant Commissioner Paul Jevtovic, International Deployment Group – the area responsible for managing Australian Federal Police (AFP) international deployments – believes that much of RAMSI’s success can be attributed to this combined approach.

“Everyone recognised very early that the problems in the Solomon Islands could not be addressed by any one arm of government, that it really needed a collective approach,” he says.

“From a law and order perspective, the combined approach of Defence and police has proven to be a successful formula. I have no doubt that without that combination, we wouldn’t have enjoyed the rapid manner in which we were able to achieve a much safer environment in the Solomon Islands.”

Assistant Commissioner Ben McDevitt, who led the police contingent of the police-led mission, echoed this sentiment during his presentation at the recent Rowell Seminar; Confronting Asymmetry: Military Conflict in the Early 21st Century. He acknowledged that having a military presence in the Solomon Islands was necessary to give the mission ‘teeth’.

Lieutenant Colonel John Frewen, who commanded the military forces deployed to the Solomons during the first four months, spoke at the same seminar. He explained that unambiguous rules of engagement were necessary in order to ensure that the military would not be portrayed as an invading force. In accordance with this, it was determined that the police would be the public face of RAMSI and would always be present when the military interacted with the islanders. As such, the military role was strictly to provide security and support for the police.

A good example of how this relationship worked is the first patrol that took place in the marketplace – only one hour and 40 minutes after arrival on the island. To establish RAMSI’s presence, two unarmed policemen – one from the participating police force (PPF) and the other a Royal Solomon Islands Police (RSIP) officer – patrolled the markets, a high-profile trouble spot. While they presented a friendly face on patrol, heavily armed riot police followed in a car with the windows up so that no guns were visible. Behind the scenes, military support was on stand-by should it have been required.

The partnership worked well. According to Ben McDevitt, there was a high level of awareness among the people of the Solomon Islands that RAMSI was arriving. In fact, people had started to hand in guns before the RAMSI contingent arrived and there were even stories of cars that had been stolen years before suddenly turning up in the driveways they had been taken from.

While there was widespread support for the mission from the general public, this was counter-balanced by the large number of well-armed militants and thugs present throughout the Solomons. For this reason, the surrender of warlord Harold Keke, was regarded as a turning point for the success of the mission.

Communicating and engaging with the people of the Solomon Islands was an important part of the mission’s success. Much time was devoted to meeting with local leaders and community members to promote an understanding of the why, who and what aspects of RAMSI.

“If we didn’t have the support of the community, law and order would still be a significant issue. But the good will, and the desire to fix the problems existed within the community itself – RAMSI built on that,” Federal Agent Jevtovic says.

“When we work in the provinces, we very much work with the local chiefs of villages and the elders, and without them we wouldn’t be successful. So it is very much a self-acknowledgment of the problem within the country, and then the willingness to work with us. I think that’s been the key to the success.”

The results achieved by RAMSI since 2003 are impressive:

- 17 police posts established throughout the Solomons within 28 days of arrival – seven with a military presence;

- 3275 weapons and 305,959 rounds of ammunition surrendered and destroyed under the weapons amnesty; and,

- more than 6500 arrests with more than 9600 charges laid.

With the restoration of law and order, the main focus is now on capacity building – this means rebuilding both the Solomons’ police force and public service.

With the restoration of law and order, the main focus is now on capacity building – this means rebuilding both the Solomons’ police force and public service.

Federal Agent Jevtovic says that Commander Sandy Peisley, who took over from Assistant Commissioner Ben McDevitt [and replaced by Federal Agent Will Jameson], is working hard to ensure this phase is as successful as the first. From a policing perspective, this means there is a focus on rebuilding the law-enforcement skills of the Royal Solomon Islands Police and restoring public faith in the force.

To date, 400 corrupt police – or 25 percent of the force – including two Deputy Commissioners, have been removed and 74 arrests covering 378 criminal offences charged. New standards of operation have been introduced and 30 recruits across all ethnic groups, including 16 females, have recently been inducted.

“I think there has been good work done, but there is still a lot of work to be progressed in continual capacity building. Mentoring and coaching are going to be a significant part of the phase that we’re in and in future phases,” he says.

According to Fedeal Agent Jevtovic, Defence’s role has been pivotal to the success, and the lessons learned for both Defence and the AFP will carry over to future missions.

“I think there has been a lot of learning take place in the two years that we’ve been in the Solomon Islands. We needed to learn and understand Defence culture and processes. Likewise, Defence has had to understand how we work as a law-enforcement agency,” he says.

“This is a whole new world for all of us. We have police going and doing work in some difficult environments offshore. Environments where some of the criminals have firepower that far exceeds some of the things that police are accustomed to in normal community policing. So it was extremely important that we had a Defence presence – it still is extremely important. Working together gives us all confidence in our ability to execute our duties on the ground. That’s something you can’t measure.

“This lays the basis for the future as well. We’ve now got a better understanding of our roles, what

we can deliver and how we deliver it. This prepares us for future Australian assistance packages anywhere in the world.”

COMMUNICATION AS A TACTIC

By Lieutenant Colonel John ‘JJ’ Frewen

In July 2003, I commanded the regional military intervention force as part of the Australian-led ‘strengthened assistance’ mission to the Solomon Islands. I was responsible for the military operations of Combined Joint Task Force 635 from 24 July until 18 November 2003 – during which time we achieved a dramatic turnaround in the law-and-order situation in the Solomons.

In July 2003, I commanded the regional military intervention force as part of the Australian-led ‘strengthened assistance’ mission to the Solomon Islands. I was responsible for the military operations of Combined Joint Task Force 635 from 24 July until 18 November 2003 – during which time we achieved a dramatic turnaround in the law-and-order situation in the Solomons.

The mission was a good example of the subtle employment of military force in support of other government agencies in a synchronised way, with careful regard to the tone of military operations and how they are perceived.

Police are the appropriate force to deal with law and order – but a firm yet friendly military force in support permitted them to do so. We were prepared for the worst on arrival but fortunately no resistance was offered.

Much of the success of this operation depended on messages – on us communicating intent, ability and

resolve while retaining public goodwill. In striving to maintain the almost universal popular support we were afforded on arrival, we placed particular focus on an information campaign with associated engagement activities.

The Special Coordinator, the Police Commander and I conducted numerous visits to remote areas to convey the mission’s aims personally. This included meetings with community groups and the all-important local chiefs to hear their questions and concerns.

While still carefully managing military presence in public areas, we conducted public displays, or open days, from quite early on in the mission. We played sports against the local community and later organised a major public concert to celebrate 100 days of the mission. We sought projects that helped people help themselves without developing an aid mentality. Unexploded ordnance disposal was one example of such a project. Another highly visible one was the sponsorship of a Clean-up Honiara Day that relied on local participation.

The open days proved particularly effective. The first open day in Honiara – held within 10 days of arrival – attracted more than 10,000 locals and cemented our firm-but-friendly reputation. Throughout these events, we promoted awareness of our technological edge over potential adversaries. Public displays of our capabilities, particularly those that could lead us to hidden weapons, such as ground detection radar and our night-vision capabilities had a profound effect on the local people and were very popular.

Our working dogs were a tremendous psychological tool that emphasised skill and sophistication. Highly trained, powerful dogs resonate deeply in the psyche of those who might face them. Similarly, our tactical unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, were also a potent psychological tool that clearly played on people’s minds. We openly displayed our abilities and the imagination of the locals took over from there.

Our working dogs were a tremendous psychological tool that emphasised skill and sophistication. Highly trained, powerful dogs resonate deeply in the psyche of those who might face them. Similarly, our tactical unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, were also a potent psychological tool that clearly played on people’s minds. We openly displayed our abilities and the imagination of the locals took over from there.

Rumours, or the ‘jungle drums’ as we called them, passed quickly through towns and villages. Soon many knew not only of our capabilities, but were trading in fictitious tales of our success in locating concealed weapons. Our decision to advertise these capabilities, and possibly overstate their merits, was deliberately taken to place pressure on those considering concealing weapons beyond the end of the amnesty. It was a gamble, which fortunately proved successful.

.

+ + +

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Share the post "RAMSI – Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands"